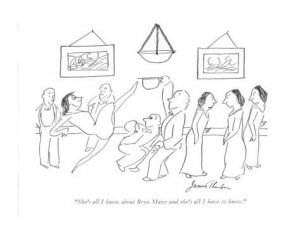

This fall I’ll be offering some informal workshops at Bryn Mawr on Latin verse composition—the translation of English into Latin verse. In view of all that has been written about the impact of artificial intelligence on academic work, I thought I’d better take another look at ChatGPT and see if it was any good at producing Latin elegiac couplets.

The short answer is, it’s not very good at all; or at least, I haven’t been able to get it to produce a line that scans, and it doesn’t seem to have much understanding of prosody or meter. I won’t bore you with the details, gentle reader, but I’ll be glad to hear from anyone who can produce a better result than I have.

At first thought, this seems puzzling. Making Latin verses, after all, seems like a mechanical process—so mechanical, in fact, that in the 1830s an English inventor, John Clark, produced a machine to do just that. (John’s cousin Cyrus founded Clark’s Shoes, which still owns the device.) If gears and wires and cogs can produce a Latin hexameter, and play “God Save the Queen” at the same time, why can’t ChatGPT?

There may be several reasons. The simplest possibility is that I’m asking the wrong questions, and that I haven’t yet hit on the combination of prompts, definitions, and rules that would lead ChatGPT to scan a verse correctly and produce metrical lines in Latin. Another possibility is that ChatGPT doesn’t (yet) have enough metadata about Latin words. It doesn’t, for example, know which syllables are long by nature. To ChatGPT, that is, venit = “he came,” with its long first syllable, and venit = “he comes,” with its short e, are indistinguishable, at least as far as their metrical shape is concerned. But the possibility that interests me most has to do with the nature of poetry and a possible limit of large language models like ChatGPT.

In poetry, words have heft. They are not mere signifiers pointing to something in the world, in the way that “cat” points to the animal curled up by the fireplace. They have a material presence, a shape and weight—even an agency–that come from the essential nature of language as sound in the air and give poetry its special powers. In Latin verse, that materiality manifests itself in the shape of words—dactyls, spondees, trochees, iambs, and the like—and in their positioning into feet and lines. In Vergil and Ovid and Horace, words don’t simply mean different things. They are different things.

For a large language model like ChatGPT, though, words are nothing except abstract symbols to be manipulated according to a set of probabilities. A word points to nothing except the word that is most likely to follow it in a particular context. There is no connection between between word and world, between signifier and signified, not even so arbitrary and tenuous a link as that between “cat” and the furry animal by the fire. Asking ChatGPT to recognize some other quality in words—their shape or scansion—and to produce Latin verse by arranging them into patterns amounts to asking it to treat words as objects and to do things with them. My attempt, at least, was no more successful that if I’d asked ChatGPT to fix my dishwasher.

When I contemplate the grim future laid out in some projections of the effect of artificial intelligence, it is no small consolation to know that words are not all there is, and that making things work in the world—fixing dishwashers, writing Latin verses, painting a picture—is still a human thing.

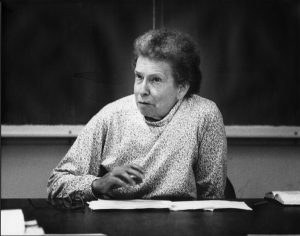

~Lee T. Pearcy

September 10, 2023