On September 11, 2001, after the second plane hit the towers, my school’s Director of Computer Operations walked down the hall and into my office. He has two degrees in classics, and so as we watched events unfold on my computer screen, we talked about Augustine’s City of God. Augustine wrote this immense treatise sometime after A.D. 410 because he wanted to understand what the sack of Rome by barbarians meant. Like Al Qaeda’s assault on New York, Alaric’s raid on Rome didn’t immediately destroy city or empire: the Visigoths broke things, took some stuff, and left after a few days. But when Augustine looked at the event through the lens of early Christianity, he saw that Rome, the city of man, was finished. It was time to think about the world in a different way.

On November 9, 2016, when it became clear that we had elected Donald Trump as the forty-fifth President of the United States, I picked up Aristotle’s Politics. Once again I wanted to know not what an ancient author had said on any particular topic—Aristotle’s opinions on some things, like slavery, fall somewhere between repugnant and obsolete—but how to think about and beyond Trump’s election. Aristotle discusses different kinds of government—monarchy, aristocracy, democracy—and the ways in which they change and decline. One thing he makes clear is that thinking about government means thinking about citizenship, and that thinking about citizenship means having an understanding of goodness: both what it is to be good at something, like being a citizen or a senator or a president, and what it means to be a good person.

Aristotle’s idea made me look at the election of 2016 in a different way. Maybe what we had seen was not a failure of politics—a matter of clueless media, FBI meddling, or midnight messages on Twitter, of getting out the vote or suppressing it—but a failure of goodness, and of education for goodness. Perhaps we, no matter who we voted for, hadn’t been very good at being citizens: at understanding each other, at looking beyond our own interests or identity, and at thinking critically and acting morally. Perhaps our educational system had failed to encourage us to do these things. Whether we voted for Clinton or Trump, we got the President that we deserve, because the candidates’ flaws and failings, their self-absorption and appeals to identity politics, are ours.

In 2001 my colleague and I weren’t much interested in Augustine’s specific ideas or his Christian analysis. We wanted to know how to think about an event like 9/11. In 2016, Aristotle’s Politics helped me think about another turning point. Americans in all periods of our history and on all sides of the political divide, from Jefferson and Adams to Noam Chomsky, who once called Aristotle “that dangerous radical,” have done the same for a long time. Perhaps a place to start in reviving what Cornel West has called “democratic soulcraft” is with continuing that long conversation that we Americans have had with Greece and Rome.

–Lee T. Pearcy

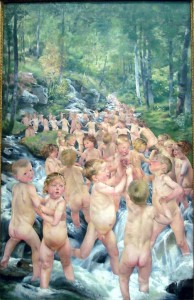

Titian certainly drew on the Imagines attributed to Lucius Flavius Philostratus (ca. 170–250). (The work may be by his son-in-law, also called Philostratus, but that possibility needn’t trouble us here.) The Imagines is an exercise in what ancient rhetoricians called ecphrasis, vivid description of a work of art. Imagines 1.6 describes a painting of Cupids or Erotes playing and gathering apples. A translation is

Titian certainly drew on the Imagines attributed to Lucius Flavius Philostratus (ca. 170–250). (The work may be by his son-in-law, also called Philostratus, but that possibility needn’t trouble us here.) The Imagines is an exercise in what ancient rhetoricians called ecphrasis, vivid description of a work of art. Imagines 1.6 describes a painting of Cupids or Erotes playing and gathering apples. A translation is