As academic specialties go, “classical reception,” or the ways in which people have “received”—enjoyed, used, learned from—the cultures of ancient Greece and Rome, seems harmless enough, and even respectable. It is, after all, the umbrella under which Classicizing Philadelphia, the project that launched this blog, shelters. Lately, though, I’ve been wondering how classical reception relates to another phenomenon that doesn’t have a good reputation at all: cultural appropriation. “Cultural appropriation” happens when someone—usually someone perceived as in some way privileged or elite—enjoys, uses, or exploits something characteristic of another culture. The term seems to have originated with academic sociologists and been weaponized by indigenous peoples with histories of colonization. Lately it’s been applied to practices as diverse as yoga, wearing sombreros, and a poem written in Black English by a white poet.

From one point of view, classical reception and cultural appropriation look a lot alike: one culture takes over something from another one and uses it. So what’s the difference, and why isn’t classical reception a bad thing? One difference is obvious: cultural appropriation is thoughtless. It doesn’t give any consideration to what the appropriated object or practice means or does in the culture from which it has been appropriated, and it does not try to give the object new meaning within the appropriating culture. The classic example is acquisition of Native American artifacts and skeletal remains by nineteenth- and early twentieth-century museums. In a museum case or on a warehouse shelf these objects become, as the title of a recent book has it, plundered skulls and stolen spirits. (By this standard, Anders Carson-Wee’s thoughtful poem in The Nation doesn’t qualify as cultural appropriation, while thinking it’s funny to wear a sombrero at your fraternity’s Halloween party does.) The best-known examples of classical reception, on the other hand, depend on thinking about the matter being received and either trying to recover its meaning or giving it a new one. Marsilio Ficino and his friends in fifteenth-century Florence thought deeply about Plato’s Academy before they imagined that they were re-creating it, and a century earlier Dante made Vergil mean something new.

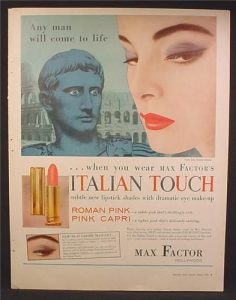

But the distinction between thoughtful reception and thoughtless appropriation will take us only so far; for one thing, some examples of classical reception are pretty lacking in thought, like this lipstick ad from the bizarre uses of antiquity in advertising that Edith Hall has been collecting in her Twitter feed lately.

Maybe this ad is thoughtless enough to qualify as cultural appropriation, or maybe the distinction between thoughtless appropriation and thoughtful reception doesn’t take us far enough. I want to suggest that another factor is in play when we draw a line between appropriation and reception: the presence or absence of a perceived cultural hierarchy.

Cultural appropriation depends on a perceived inequality. The culture doing the receiving is not only clueless about the cultural significance of the received material but also in a position to be clueless—the position of acknowledged cultural or political or social superiority. The culture whose products are being appropriated, on the other hand, is acutely aware of the unequal status of the two cultures. Only people who are aware of their lower position in a hierarchy of cultural status can complain of cultural appropriation or feel the pain it causes. Having the Elgin Marbles in London does no harm to ancient Greece, but the modern Greeks can feel aggrieved because they believe that bullying Britain took their treasures when they were weak and oppressed by the Ottoman Empire. They are caught in a trap: every complaint about cultural appropriation affirms and reinforces their perception of inferior status. (Arguments about whether what Elgin did was lawful or not are another matter.)

Reception, in contrast, depends on an understanding that the culture being received will not be diminished or harmed by the other culture’s use of it. And implicit in that understanding is an assumption, which doesn’t have to be explicit or even conscious, that the culture being received is in some way equal, or even superior, to the one doing the receiving. It’s like potlatch, or Homeric gift-giving: giving only augments the prestige of the giver, and receiving a gift acknowledges the giver’s status. No one has yet (to my knowledge) accused Julia Child of cultural appropriation, first because cooking French recipes does no harm to the glories of la cuisine française, and second because no Frenchman believes that French culture is inferior to or of lesser status than American culture. It may be otherwise with burritos or collard greens. Ancient Greece and Rome can be objects of reception not only because they are safely in the past and can’t object, but because of the perception that their material, literary, and political cultures are worth receiving and beyond harm. Every act of reception, even a lipstick ad, confirms their status.

–Lee T. Pearcy

9/2/2018: And now Kwame Anthony Appiah has said it better, as usual, in this WSJ piece.