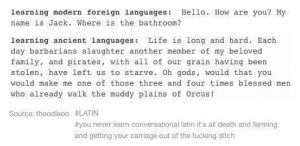

A recent post on Twitter tried to sum up the difference between learning ancient and learning modern languages:

True enough, but it didn’t touch on one of the biggest problems facing anyone who tries to teach students, or at least American students, about the ancient world: what do we say about slavery? And how do we handle sentences like this, from the Cambridge Latin Course: “Ego servo epistulas dictabam,” inquit Caecilius?

The first thing to do is to get rid of the translation, still found in a few older textbooks, of servus as “servant.” But then an American teacher is left with two hard facts: the ancient world depended on slaves, and we have our own contentious history of slavery. Our students know about slavery. They know that slavery is wrong, and when they imagine slavery, they imagine a world of black slaves and white masters. It can be a challenge to help them understand the complexities of ancient slavery.

The past is a foreign country, of course, and every word in that sentence from the CLC, even ego, means something different from its standard English equivalent. That’s because slavery in the ancient world was different—perhaps even a different institution—from slavery in the United States before the mid-nineteenth century. At least three features of ancient slavery need explanation: slaves were invisible, they were ubiquitous, and they did work that we do not associate with slaves. Sometimes thought experiments help students understand what these things meant.

I’ve tried asking students how many intelligent devices are in our classroom. Usually the number surprises them—each student has a phone, and maybe a laptop, and there is the classroom computer, and so on. “Those are the slaves,” I say, and to the Romans, slaves, like our smartphones, were little more than intelligent devices, and worth about as much attention. Most of the time, they were, if not actually invisible, unseen.

And like our intelligent devices, they were always there. In our society, having sex is something that normally happens in private, in a space with only two people present. This fresco from the House of Caecilius Iucundus at Pompeii is one of several ancient representations of people engaged in this intimate activity with a third figure in the background—a slave, smaller and faded, almost but not quite invisible. The two people in the foreground aren’t paying attention to her (I think it is), any more than two people similarly occupied nowadays would pay attention to a television or computer.

Students have difficulty grasping what it was for a free Roman to live in a world where he or she was almost never alone, never in a room or outdoors without someone else. (For today’s students, though, being alone might have been something like being without their phone!) It’s probably not a good idea to introduce scenes like the one from Caecilius Iucundus’ house into a school classroom, but explaining that being alone was an untypical experience for most Romans can help students understand, for example, why Ovid’s Ariadne in Heroides 10 seems so distraught when she is abandoned by Theseus on Naxos. Part of her hysteria is Ovidian hyperbole, but some of it is an understandable Roman response to solitude.

Thinking about the kinds of work that slaves did in the Roman world underscores the difference between ancient and modern slavery more than perhaps any other feature. It can also make students uncomfortably aware of some features of their own world that often escape notice. Roman slaves managed estates, drew salaries (their peculium, which, like their persons, remained their owner’s property but could be used to buy their freedom), taught in schools and tutored Roman home-schoolers, treated patients, and did all sorts of work that we don’t associate with slavery. I invite students to imagine a time-traveling ancient Roman trying to figure out how our world works, and who works in our world; for myself, I often imagine riding the bus with Cicero. SEPTA’s route 44, which goes from the western edge of Philadelphia almost to the Delaware River on its eastern border, is a good place to start.

Cicero would have had no difficulty identifying the slaves on that ride. There’s the bus driver, for one, and the people in teal jackets from the Center City District pushing their giant vacuums, and the policemen, and the firemen in their station at 21st and Market –clearly public slaves, servi publici, and so perhaps a bit better off than others. There are also the clerks glimpsed inside stores, and the servers in restaurants. And what about all those young men and women in business suits scurrying in and out of the tall buildings in the financial district? For Cicero, in fact, almost everyone who did some kind of work, and especially anyone who worked with his or her hands, would seem to be a slave. Imagining a bus ride with Cicero can help students think about a fundamental difference between the Roman world and ours, and about people who are often unnoticed and everywhere, doing the necessary work of society.

–Lee T. Pearcy

Follow-up 8/24/2018: Caitlin Rosenthal writes on continuities between American slavery and modern management, here.