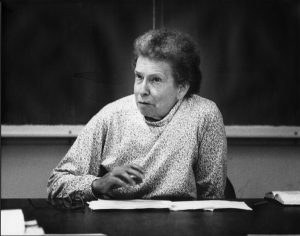

Mabel Lang taught at Bryn Mawr from 1943 until 1988, and for nearly every semester of those forty-five years she taught elementary Greek. The course became so popular that she often taught two sections, one at eight o’clock in the morning and the other at nine. You can read about her here.

I thought of Mabel the other day when this essay by Blake Smith appeared in the Chronicle of Higher Education. It has to do with the writing centers that feature on nearly every college campus these days, and by extension with the teaching of writing generally. In the writer’s view, college writing centers are ineffective, jargon-infested hives of neo-liberal practice, like the assertion that a good essay “delivers value” to its reader, and of progressive theory about race and capitalism. (Quite how neo-liberalism and woke piety manage to sit in the same room goes unexplained.) They fail in their plain duty, to teach students how to write.

I know little about teaching English composition, and the merits of writing centers are not my concern here. I want to think instead about a two-fold assumption that receives only passing attention in Smith’s essay: that the actual delivery of instruction in composition is in the hands of graduate students, adjuncts, and other dwellers on the lower rungs of the academic hierarchy that culminates in tenured full professors, and that instructors of composition and other elementary subjects wish they were somewhere else. As Smith puts it, “instructors at writing centers, chafing at their low status within their institutions and fields, and resenting that they are often called upon to bring students up to speed rather than to do what is perceived as more serious intellectual work, try to give some gravitas to their positions by charging the simple but difficult work of writing with a complicated new conceptual vocabulary or pompous assertions of their own social importance.”

This hierarchical dynamic certainly holds true for my own field. In most colleges and universities, including Bryn Mawr, tenured faculty do not teach the early stages of Greek and Latin, and most would be horrified, I think, at the thought that they should. Recently I suggested to one of my senior colleagues, a retired full professor, that it would be good if people like her brought their accumulated wisdom to the teaching of elementary or intermediate languages. She opined that she didn’t want to take a job away from the graduate students to whom it rightfully belonged. A few years ago, I interviewed at a large, midwestern state university for a job overseeing and guiding the graduate students who taught elementary and intermediate languages. During the interview, I suggested that one of my goals would be to have every member of the department, including senior faculty, teach intermediate Greek or Latin at least once every five years. The learned men and women sat in stunned silence before moving on to the next question.

Many senior college and university classicists, I suspect, have stopped thinking of themselves as language teachers. Their calling, they argue, is a higher one: to convey to students the complex ideas and critical theories that constitute the conversation of the humanities in modern universities. They have spent a lifetime, they might argue, becoming expert in Plato’s metaphysics or ancient religions or Roman political theory, and in the modern ideas, from Althusser to Žižek, that shape those topics. Why should they waste their time with the ablative absolute?

I can think of three reasons: first, to show that they care about the ablative absolute; that is, that they care about the close, analytical reading that lies at the heart of classical studies. (Assuming, of course, that they do believe that—there are signs that the belief is not universal.) Second, to show that beginners and beginnings matter, and so that a first-year student beginning Greek is as important to them and to their professional ambition as a graduate student writing a dissertation on Pindar. (This was the message sent by Lionel Trilling every time he taught a section of the required freshman humanities course at Columbia.) Third, because to teach anything is to set your person before students as an example, and beginning students may need the example of senior scholars.

Is it a waste of time and talent for tenured full professors at the height of their scholarly prowess to teach Greek 101? Mabel Lang didn’t think so.

~Lee T. Pearcy

Update 2/8/2023: Above I wondered “how neo-liberalism and woke piety manage to sit in the same room ” A hint of an answer appeared in this essay, also from the Chronicle of Higher Education:

DEI Inc. is a logic, a lingo, and a set of administrative policies and practices. The logic is as follows: Education is a product, students are consumers, and campus diversity is a customer-service issue that needs to be administered from the top down. (“Chief diversity officers,” according to an article in Diversity Officer Magazine, “are best defined as ‘change-management specialists.’”) DEI Inc. purveys a safety-and-security model of learning that is highly attuned to harm and that conflates respect for minority students with unwavering affirmation and validation.

(Anna Khalid and Jeffrey Aaron Snyder, “Yes, DEI Can Erode Academic Freedom,” Chronicle of Higher Education 2/6/2023.)